In our cold, contemporary era, the amassment of immeasurable wealth within the global capitalist order has reached unprecedented heights of human degeneracy. Mindless consumption and its poisoned fruits have invoked the fury and lust of an insatiable death drive. Accumulation and its enjoyment continue to spur catastrophe to varying degrees of intensity and violence. Many have met their fates at the hands of their greed.

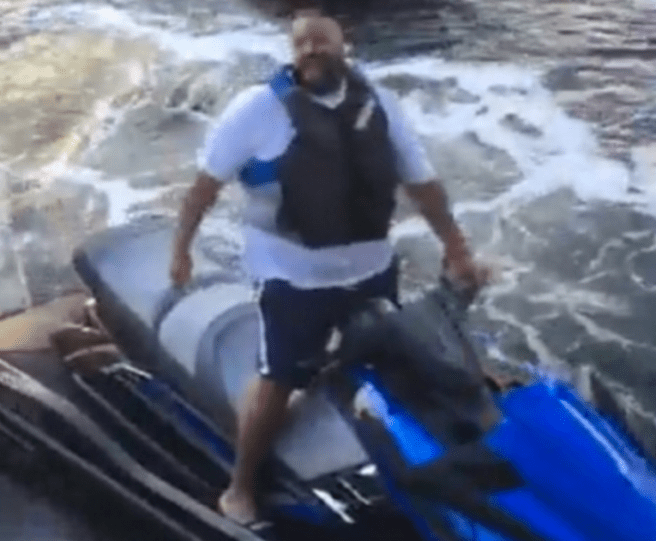

Engrossed in the stormy eye of Capitalism and the perpetual production of crisis, we find its true idol: a piggish yet charismatic businessman, adorned in gold, roaming without objective in a multi-million dollar oceanside mansion who came from nothing. He, filled with a hunger for adventure, walks to his dock and mounts his jet ski at full speed on a near-daily basis, often encountering law enforcement, where he is protected from punishment by equal parts charisma and the influence of his great wealth. He is beckoned by a sweet Death whispering in his ears, its bony, skeletal fingers grazing his freshly-cut head:

“Further… further… forget the moment… there is no present… only the End…”

The rider smirks, and entertains the uncomfortably convincing voice, traveling unflinchingly into a watery abyss. It isn’t long before he is lost at sea, low on gasoline, destined to met an unfortunate fate. Here, there is no capital, but there is a familiar feeling of excess: a boundless ocean, blackened by a fresh, night sky. It is cold—colder to the unclothed. Starvation is imminent, if sea creatures don’t get to him first. Perhaps a storm will brew, separating him from his vehicle, drowning him—destined to quietly meet millions of bodies that have met similar fates. A slow but imminent demise documented on video, another life claimed. An all-too-common conclusion for an ordinary man.

Defiant triumph.

Somehow, the expected story is unexpectedly altered.

Our hero, after his risky pursuit of Death, manages to arrive to his grand mansion completely unscathed, ready to sleep it off. The vainglorious capitalist evades Death, not through purchasing power, but through an extraordinary state of subjectivity.

* * *

The Khaledian school of psychoanalysis has emerged as a post-structural reconceptualization of Lacan’s oft-considered controversial response to Freud. In a refreshingly radical depature from the kind of teaching contained in Lacan’s famous Écrits, Khaled and his subdiscipline opt for informal lectures—Cloth Talk and Hammock Talk—and a minimalist, quasi-Nietzschean aphoristic approach to illuminate his psychic praxis.

Who is the Subject?

In Khaledian psychoanalysis, there is no static subject that occupies an experience at a given time; there is no mere “I.” The subject is the We, the You, and the I, a Borromean knot of identity. The We may be interpreted as the de facto primary subject, but there is no hierarchy in the Khaledian school. We The Best is the familiar aphorism guiding an interpretation of the Subject; there is only We, and We are the Best—We, by virtue of our collectively, have attained Perfection—there is no incompleteness. Perfection, then, is, perhaps, the neo-Symptom.

Khaledian psychoanalysis, then, has a complicated relationship with Desire—can We want if We are the Best? Do We demand Perfection if We have achieved it? Do we demand anything if we are Perfect (cf. “Another one”)? The Subject is not alone, but belongs to an interconnected network of human experience. Khaledian psychoanalysis, in a departure from its Lacanian sibling, is quite curiously inspired by Eastern philosophy, with an appreciative nod to the Hegelian notion of The We Is The I and The I Is The We. Yet, is there critical self-reflection among such a split subject in the Khaledian school? Almost inherently so.

Chef Dee as analysand

As a particular stand-out case, Chef Dee is a curious case within the network of Subjects. This Being has transcended Desire—she is Pure Production, entertaining the Performance of Success through culinary mastery.

The absence of desire.

An entity utterly restricted to cooking egg whites and turkey bacon, Chef Dee may long for More, but there is no Desire: she, in her soulless candor, merely expresses information. We The Best, and Chef Dee is aware, and acts within the network. Chef Dee is relegated to her status, void of Want, a Limitless Machine of—very fittingly—consumption. This is especially apt as a metaphor when one recognizes that Chef Dee’s role in the Khaledian subject is to reinforce the largeness of the Idol—the Pure Image of Capitalism in an Age of Gluttony. This is pure ideology!

* * *

Beyond the We, it is recognized that the We may split into the You—a dissociation of the group to encourage communal Unity. A familiar aphorism for this perspective is You Smart, You Loyal—a symbol of undeniable praise. Is the We constructed at different levels—rather, is there a Big We and a little We, distinguishable from the Lacanian Big? It is attractive to think that the We can Split off into the I and the You, as evident in a third aphorism, I Appreciate You. This is, of course, another positive construction of undeniable praise. The reasons are unnecessary—it is purely ideological. There is never a Because in the aphoristic discipline of Khaledian psychoanalysis, and with what may be a very good reason: Perfection is achievable by all when it is radically unconditional!

Of particular curiosity is the I, which may exist out of necessity to reinforce the individual’s Love of the You as it exists in the We. Self-love and appreciation, then, is a function of self-acceptance, and a reflection of a greater structure of empowerment. Again, it is not static, but there is no grammatological suggestion that it is endlessly dynamic. I Changed Alot, a fourth aphorism, expresses that there were historical conditions at work in which the I emerged. How interesting, then, that the aphorism is not “I’m Changing Alot!” Perhaps the aphorisms, much like the Subject, exist within a relational network, and the end-result of change is Perfection—being the Best among a collective Subject. Is Perfection, then, static? Khaledian psychoanalysis has no evident answer; however, it can be assumed that different standards of perfection may exist, as clearly as there are different variations of infinity.

The Other

What of the Other? Khaledian psychoanalysis has a Lacanian equivalent: They. There is no Other, but the big They, that which destabilizes your social relations and wants to see you fail. The They is against nutrition, The They is against success, The They is against happiness and enjoyment. The They is unspeakable, and exists in a universe equivalent to that of the Lacanian Real—the traumatic space where the symbolic falls apart. Khaledian psychoanalysis refuses to acknowledge what the They is beyond the They merely being what it is: the They.

To frame it ideologically, The They is clearly a sullen specter of anti-capitalism. It is denial of fulfillment, halting the tip of the iceberg of jouissance, a symbol of pure static, desireless Being. It is a void on the Opposite end of the metaphysical emptiness of pure material; a death-like void where there is no Space but only Time. The They is the anti-Perfection, the anti-Blessing. They don’t want You or We to be the best, or to be anything but Be. In that sense, the They is the diametric opposite of the Subject. Khaledian psychoanalysis implies that They is meant to break down the Subject, but never beckons the Subject away from the They, but encourages the Subject to act against the Will of the They—to perform Perfection at all times, to be Smart and Loyal! Khaled himself is on an ideological crusade to digitally document his success to the chagrin of They, employing the excesses of capitalism to do so, as it is, in the Khaledian school, the basest and most obvious indicator of Success.

Is Khaledian psychoanalysis a positive philosophy?

He’s content.

Khaledian psychoanalysis is incorrigibly liminal, caught between Good and Bad. Its irreconcilable ties to capitalism situate it—at least in our contemporary context—as an extremely violent and deadly force, both undeniably to anyone outside the Subjective network, and arguably to those within it.

Yet, Khaledian psychoanalysis also sees the universal, radical acceptance of the We, the appreciation of the You, and the unadulterated love of the I. Even functioning within a violent capitalist structure, the positivity of Khaledian psychoanalysis is extremely promising—and even subversive in its acceptance of what seems to be an omnipresent, irremovable evil.

Is Khaledian psychoanalysis tenable? One is tempted to say yes. Only time will tell.